Written by Richard Romano, Industry Analyst. Article first appeared at www.PrintPlanet.com and can be read here.

“Stealing work from offset” has become a common phrase in the industry these days, often heard in contexts ranging from small- to wide-format digital printing, and even in some parts of the packaging market.

It’s a desire—or a fear, depending upon whom you ask—but what it means is that customers can get the quality of offset as well as the short-run (even run-of-one) benefits with digital printing. It’s often thought of as a “best of both worlds” approach.

After all, print service providers today have to be flexible, and even if they still do a substantial offset business, they may find that they are turning work away if it doesn’t suit the press(es) they have. And the challenge they may have in acquiring equipment to do that short-run work is finding a system that will produce quality good enough to match what has come off the offset press. This is especially true if they are doing different types of print work for the same customer, and certain colors and other qualities have to be comparable, if not identical, from one run to the next.

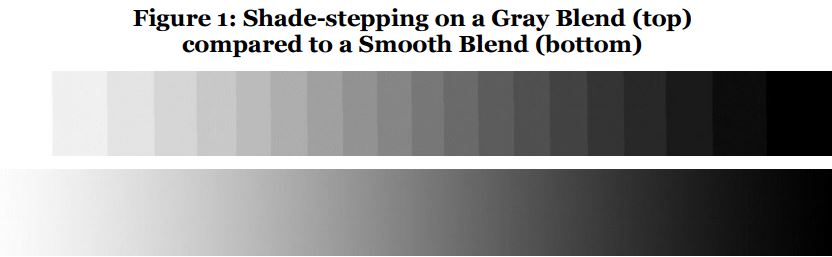

There are many aspects to what we think of as “image quality,” but one place where many digital printing systems fall down is in the unfortunate tendency for printed materials to exhibit banding, aka stepping, or the blatant visibility of the discrete steps in a gradient. In other words, the fine shades don’t flow “seamlessly” from one to the next. The reason this occurs is essentially a function of data—or, rather, of not having enough of it. In this case, “data” and “gray levels” are synonymous.

A Shallow Look at Bit Depth

Let’s have a brief look at a topic from Digital Imaging 101: bit depth.

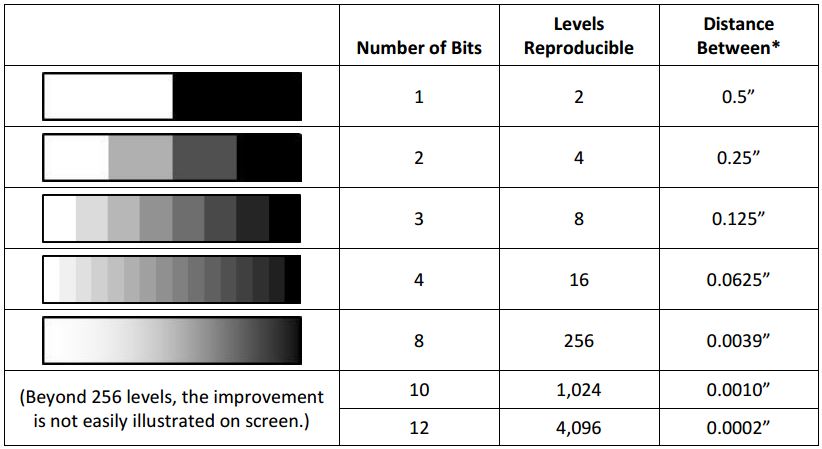

The greater the bit depth that an imaging system can produce, the more gray levels are available for display. A 1-bit image only offers two gray levels: black or white. If a digital printing system could only produce 1-bit images, you could print text and simple shapes, and that’s about it. A 2-bit image ups the quality just a tad by giving you four gray levels to play with. By the time you get to 8-bit images, you now have 256 shades of gray.

Is that enough to eliminate banding? Not always. Some front ends and print engines have clever ways of positioning dots to minimize the appearance of banding, but nothing can take the place of simply having more information to work with. Being able to produce 10-bit images gives you 1,024 shades of gray—that’s four times the number of gray shades as 8-bit images. And the more gray shades, the smoother the blend and the less likely that banding or stepping will be perceptible—or exist at all. That gets the image quality closer and closer to the quality of offset. (InfoTrends has produced a handy white paper that explains all of this in far greater detail.)

Enter Ultra HD

Ten-bit images are in fact those produced using a new technology called Ultra HD, utilized by Xerox’s Versant family of digital presses. At the moment, there are two entries in the Versant lineup. The Versant 2100, which launched in spring 2014, is a 100 ppm color digital press, with a recommended monthly volume of 75,000 to 250,000 pages. At the other end of the spectrum, the Versant 80, which launched in North America in April 2015, is an 80 page-per-minute (ppm) toner-based color digital press, with a recommended monthly page volume of 80,000 pages. Both models feature Ultra HD technology, which is unique to the Versant family.

Becoming Conversant

As a result, Ultra HD technology offers print service providers the ability to produce offset-quality work while taking advantage of all the benefits of digital printing. And while it’s tempting to think that this kind of image quality is only suited for high-end applications that require photographic quality imaging, banding/stepping and lack of smoothness in gradients are problems that can adversely affect virtually any commercial job or application, especially where customers’ logos may be involved. This can either help “steal work from offset” or, in fact, complement offset.

“[Versant] really is the pressman’s press,” said Brian Segnit, Worldwide Product Marketing Manager for Xerox. “It handles all digital print applications. I get offset quality, and I can do a run of one, 500, or 1,000, whatever the break-even point is.”

“The Versant 2100 production capabilities are a perfect fit for getting more high quality, short run and quick turnaround jobs out every shift,” added Mary Roddy, Global Product Marketing Manager for Xerox. “Ultra HD resolution should open the doors to customers that perhaps [print service providers] haven’t been able to satisfy in the past.”

The Versant family also features one other element that is in demand in virtually all applications, be they analog or digital: automation. At the same time, the Versant family is, as Segnit describes it, “push-button easy to use.”

So whether you are looking to in fact steal work from offset or complement/supplement offset printing with high-quality digital, a technology such as Ultra HD offers a more appealing value proposition.

Comments are closed.